Your Civil War Geek Installment IX.

Use and Limitations of Intelligence During the Civil War.

Anyone that seriously devotes time and energy to studying the Civil War, will realize that the type of intelligence gathered and employed by commanders and used by chiefs of state during the war was, more often than not, flimsy. It’s very easy to armchair quarterback mistakes made between 159 and 155 years ago from the comfort of our climate-controlled dwellings. While military science experts today can easily see the faults and flaws committed by the actors on that great stage, it was much harder for the players in that time to effectively gather, interpret, and employ that intelligence. Today, I’m going to attempt to shed light on the way intelligence was gathered, interpreted, and employed during the Civil War.

Before, I go too in depth into this post, I want to use modern terminology to explain types of intelligence use by the military.

- HUMINT: Human intelligence, first, second, or third person information gathered from actual living breathing humans. In the War, this would include scouts, runaway slaves, deserters, soldiers, civilians, refugees, and spies (Department of the Army, 2004).

- IMINT: Imagery Intelligence: IMINT was not really applicable during the Civil War because Cameras of the time required and absolutely motionless platform, 10-15 seconds of exposure to light, and almost no ability to enhance images (Department of the Army, 2004). Even military produced topographical maps were at best a derivative of HUMINT back then.

- SIGINT: Signals Intelligence: During the Civil War wide-spread use of the telegraph was used and visual signaling such as Wig-Wag flags were employed (Department of the Army, 2004). Tapping into telegraph lines was a tactic frequently used during the Civil War.

- CI: Counterintelligence: This craft is devoted to ferreting out enemy intelligence gathering operations and interrogation of civilians, soldiers, and known spies. Both sides employed CI but just didn’t call it CI (Department of the Army, 2004).

Without going into a Battle Staff lecture on intelligence, I’m going to use specific examples and events during the Civil War, to attempt to convey some understanding of the impact of intelligence during this conflict. Very little real time intelligence was available to commanders in the Civil War until two armies were within spitting distance of one another (figuratively), compared to conflicts of today. Today we have radar, satellites, drones, and signal receivers which seem to provide modern commanders with too much information in some instances.

Modern armies focus more on small unit tactics, squad, platoon, and companies, whereas the Civil War focused on larger units, squadrons (cavalry), regiments, divisions, brigades, corps, and armies. Below is a quick breakdown of these formations so the novice reader can appreciate the scale of battle in the Civil War. For the purpose of this example between 80 and 100 men comprised a company (Hardee, 1990). This figure is not exact because recruitment and organization was not always uniformly consistent throughout both sides during the war.

Unit Approximate Number of Persons Commanded by:

Regiment 10 companies (800-1000 men) Colonel or Lt. Colonel

Brigade 2-5 regiments (up to 2600 men) Brigadier General*

Division 2-4 brigades (up to 8000 men) Major General*

Corps 2-3 Divisions (Up to 26,000 men) Major General*

Army 3 or more corps (Up to 80,000 men) Major General* (American Battlefield Trust, 2020).

*In the Confederate army, due to size restrictions, a brigade could be commanded by a Colonel, a division by a Brigadier General, a Corps by a Lieutenant General, and Army by a by a Lieutenant or full general. The Union Army general officer ranks during the Civil War only went as high as Lieutenant General.

So, now that the sheer size and scale of units has been established, we can understand the type of numbers which were of interest to 19th century commanders. Today, small unit operations are very significant, in the Civil War, cavalry and irregulars were not as highly weighted as larger units were in the overall intelligence picture. Since it was difficult to hide large unit movements, in many cases small unit movements were dismissed out of hand when reported (Griffith, 2001). That is not to suggest they were not relevant or important to commanders, but unlike Napoleonic cavalry, they were not used as a major arm of combat power. There were instances were cavalry performed enormous feats such as J.E.B. Stuart’s ride around the Army of the Potomac, or Nathan Bedford Forrest’s and John Hunt Morgan’s raids, and John Buford’s delaying action at the Battle of Gettysburg (Foote, 1986). While individually successful and impactful, cavalry as a whole was often mis-used or ignored by some commanders. The cavalry’s purpose in the Civil War, was flank protection in battle, screening movements of larger units, and intelligence collection for the field commanders. Collectors of intelligence during the Civil War tended to be fixated on the large units (Fischel, 1996).

Today, every soldier is in basic training is taught the fundamentals of how to report observations of enemy movements in the form of a SALUTE report (Size, activity, location, unit (size or actual designation) time, and type of equipment) In the Civil War, basic training was the company drill practiced by both side in the form of School of The Soldier. When not marching or fighting both sides drilled the School of the Soldier rigorously (Hardee, 1990). After the fighting started in 1861, neither side had the luxury to spend the nine weeks devoted to basic training as we do today. Soldiers in the Civil War were expected to march, stand picket duty, load and fire their weapon as part of a larger unit, and drill. As armies drew closer, both before and after battles, pickets from both sides would regularly fraternize when their senior officers were not around (Foote, 1986).

Rose Greenhow:

(Ms. Rose Greenhow. Between 1855 and 1865)

The outbreak of the Civil War placed the capital of the United States in a slave holding the slaveholding state of Maryland, with a significant portion of its population sympathetic to the Confederacy (Catton, 1967). One of the primary sources of intelligence to the Confederacy early in the war was the Confederate spy, Mrs. Rose Greenhow. As far as the Confederacy’s intelligence collection was concerned Ms. Greenhow was much more effective than Pinkertons was for the Union. Rose was widowed when her husband Robert Greenhow, a State Department employee was fatally injured in San Francisco (Fischel, 1996). Prior to the War, she settled in the D.C. area and made personal social acquaintances with politicians and families of pro-union, and secessionists political bents. Her most significant contribution to the Confederacy was information she provided General P.T.G. Beauregard prior to the battle of Manassas/Bull Run in July 1861. Ms. Greenhow’s intelligence on the movement of McDowell’s Army into northern may have empowered the Confederacy to make necessary changes to troop dispositions, but famed reports to Beauregard prior to First Bull Run had significant gaps in time. The battlefield exploits of men like Jackson, the greenness of soldiers and commanders on both sides, and the fog of war had more to do with the victory than Ms. Greenhow. There were opportunities on both sides for victory, success in that battle came down to who panicked first, and in that first major battle, sadly, it was the Union which set the tone for other failures in 1861 and 1862 (Griffith, 2001).

Ms. Greenhow certainly provided the Confederacy with actionable HUMNT early on in the War ,but she was compromised by Union intelligence operating inside D.C. and kept under observation until her arrest in August of 1861. Many historians have jumped on the “Greenhow” bandwagon, over rating her contribution to the Confederacy’s victory at Bull Run/Manassas. These contributions are based on accounts of questionable veracity, namely Greenhow and Allan Pinkerton (Fishel, 1996). Because Greenhow’s exploits or as historians should say, alleged exploits, make for thrilling reading, people through mostly embellishment and word of mouth continue to make her contributions much larger than they actually were. Pinkerton, who was famous for providing unreliable intelligence, was a consummate self- promoter. Greenhow herself, believed she was much larger a figure in the confederacy than she was (Fishel, 1996). Greenhow was ultimately banished to the South where she could do no harm and provide less of a distraction to the Union.

Intelligence failures in the Civil War sometimes were biproducts of personal relationships between the collector and commander, rather than the veracity of the intelligence collected. In December of 1860, following the election of Abraham Lincoln, a moderate Republican, South Carolina became the first state to succeed from the Union. James Buchannan, the outgoing president, did nothing and was content to let his successor deal with the division of the nation (Foote, 1986). John B. Floyd, Buchannan’s Secretary of War, actively used his office to position army supplies and weaken forts located in southern states, where they could easily be acquired in the event of war. In May of 1861 Floyd was commissioned as a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army.

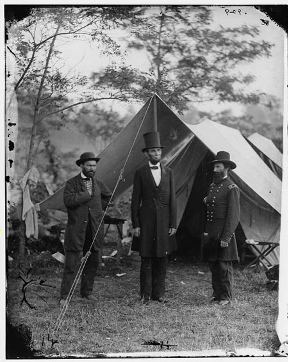

(Gardner, 1862) Allan Pinkerton far Left, Abraham Lincoln Center, and Major General John A. McClernand Right.

From the very beginning of his presidency, Lincoln became acquainted with a Scottish immigrant turned railroad detective by the name of Alan Pinkerton. Pinkerton provided security for the President Elect during his trip from Springfield, Illinois to Washington, DC (Catton, 1967). Pinkerton, though successful in this mission, would prove woefully inept in his later role as Head of Union Intelligence.

After the battlefield setbacks in late 1861, Lincoln appointed McClellan as General in Chief of the Union Armies. McClellan, an effective organizer and motivator, was not in any stretch of the word an aggressive combat leader. McClellan relied on Pinkerton to provide reports of Confederate troop strengths, fortifications, and movements. Pinkerton’s numbers were often severely inflated. Pinkerton relied exclusively on HUMINT gathered by deserters, runaway slaves, and informants (Fishel, 1996). Pinkerton created an elaborate staff of agents who operated behind Confederate lines. In some instances, his agents were able to get close to key administration officials. The problem with Pinkerton’s intelligence was that it was often inflated, his observers were easily fooled, and they did not take the time to individually validate the information they gathered before reporting. Since McClellan trusted Pinkerton’s information, he was doomed to fear a phantom force rather than appreciate his own numerical advantage (Catton, 1990).

In the late spring of 1862, after months of vacillating, Lincoln finally grew tired of McClellan’s delays. McClellan, possessing between 100,000 to 130,000 troops, persisted with the excuse that he was outnumbered. His correspondence with Lincoln from February to April was insistent, (to the point of insubordination at times) that he required more troops to confront Pinkerton’s estimate of 200,000 confederates. (Donald, 1995). As a result of McClellan’s reluctance, he was demoted to just the commander of the Army of the Potomac rather than General in Chief (Foote, 1986).

Following the Major General Pope’s failed campaign culminating in the 2nd Battle of Bull Run (or second Manassas), McClellan was restored to command of all troops formerly under Pope. Not learning from his lessons during the Peninsula Campaign, McClellan once again listened to Pinkerton’s inflated estimates. In early September 1862, while stopping near a former Confederate camp site, two Indiana soldiers stumble across cigars wrapped in a document. As it turned out, the document was a copy of Robert E. Lee’s Special Order 191 which outlined part of his invasion plan for Maryland (Priest, 1992). McClellan was supremely pleased with this intelligence coup, was reported to have said, “Here is the paper with which, if I cannot Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home” (Murfin, 1993, P 133).

Over the next two week, McClellan’s forces would fight at South Mountain and Antietam Creek in Sharpsburg, MD. Both would go down as Union successes, but McClellan failed to capitalize on his success failing to employ all his forces at Antietam and allowing Lee’s army to escape back across the Potomac after the battle. Convinced once again by Pinkerton that Lee had numerically superior forces, he remained at Antietam, licking his wounds and sending excuses for his army’s lethargy to Lincoln. After almost five weeks of inactivity Lincoln’s patience was at a breaking point. After receiving an excuse that McClellan’s horses were fatigued Lincoln sent the following telegram.

“Telegram to General George B. McClellan War Department, Washington, October 25, 1862

I have just read your dispatch about sore-tongue and fatigued horses. Will you pardon me for asking, what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigues anything?

- Lincoln” (Lubin 2005, P. 365.).

The next month McClellan was replaced by his friend Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac. In his tenure of command of the Army of the Potomac, McClellan saw shadows and apparitions of Pinkerton’s construction, which played into his slow and deliberate way of thinking. Lee had between 45,000 and 60,000 thousand troops at any given point who were fit for battle (Priest, 1992). McClellan had a large portion of his army that had not seen action during the battle. He retained these men in reserve believing he would need them if Lee launched a counterattack with his phantom forces. Had McClellan used cavalry effectively, or employed military scouts rather than a close friends network of amateur spies, his chances of defeating Lee would have been much better.

In the western theatre of the war, exploitation of SIGINT was almost the downfall of two leaders early in the war. Many armchair historians love to jump on the presumed “fact” that Ulysses S. Grant was a drunkard. Historians, such as Catton, Foote, and Chernow have almost conclusively disproved this claim, but it is a theme that some historians love to return to, time and time again (this will be the subject of a future post). Why it is mentioned in this instance was Grant’s relief by Halleck following the Henry Donelson campaign. While it is not a secret that Halleck did not like Grant, following Henry Donelson, Halleck believed, erroneously, that Grant was not transmitting returns on his army’s strength and dispositions and was drinking again. In truth, a telegraph operator, who was also a confederate sympathizer, was not relaying those dispatchers forward to Halleck (Catton, 2000). There was no way, Grant, from his position in northern Tennessee could be aware of the actions of a telegraph operator in St. Louis. As a result, Halleck had relieved him, and was authorized by McClellan (then General in Chief) to place Grant under arrest if necessary.

Major General Don Carlos Buell was, like McClellan cautious, but unlike McClellan, Buell was hampered by irregulars with a keen appreciation of how to exploit SIGINT to their advantage. During John H. Morgan’s first raid into Kentucky, the took inordinate pleasure in intercepting Buell’s telegraph communications on a regular basis (Dyer, 1999). At one point the Brash Morgan even complained through an intercepted telegraph line complaining of the quality of horses he captured from Union forces (Foote, 1986). Buell, perhaps unfairly, earned a reputation as being the western theatres equivalent of McClellan. Unlike McClellan, Buell operated in a state, while nominally neutral, was in practice a hotbed of irregular activity.

Like commanders today which are subjected to incalculable quantities of intelligence, in the Civil War the challenge was to make since of intelligence and rapidly apply it to military operations. Unlike modern commanders, Civil War commanders mostly depended on HUMINT and validating that intelligence in a timely manner was problematic and costly in terms of lives. Cameras of the time could not be operated from areal platforms such as Professor Thaddeus Lowe’s balloons (Marvel, 1991). In the Civil War observes would sit in a basket and relay observations to people below. With the primitive optics of the day, this proved problematic and the Balloons, as in World War 1 over 50 years later, provided excellent targets for opposing forces on the ground.

(1862) Fair Oaks Untied States Virginia, 1862

So, my fellow armchair generals, remember intelligence is ever evolving, and as it evolves, it often proves more challenging in its processing and interoperation. Commanders today who have access to almost, if not instantaneous, intelligence, still make fundamental errors. In the Civil War, even with its relative boom in technology, most intelligence was HUMNT and that has always been the most difficult to read.

Sincerely, Your Civil War Geek

Patrick D. Stoker, PhD

US, Army (RET). Firefighter/AEMT

References:

American Battlefield Trust. (2020). Civil War history: Civil War army organization. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/civil-war-army-organization

Catton, B. (1990). The Army of the Potomac trilogy: Mr. Lincoln’s Army. New York, NY: Archer Books.

Catton, B. (2000). Grant Moves South. New York, NY: Castle Books.

Catton, B. (1967). The coming fury: The centennial history of the Civil War, volume 1. New York, NY: Washington Square Press.

Department of the Army. (2004). FM 2-0: Intelligence. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army.

Donald, D. (1995). Lincoln. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Dyer, C. (1999). Raiding strategy: As applied by the western Confederate cavalry in the American Civil War. Retrieved March 24, 2009: 263-281. http:www.proquest.com.ezproxy.apus.edu.

Fishel, E. (1996). The secret war for the Union: The untold story of military intelligence in the Civil War. Boston, MA: Mariner Book.

Foote, S. (1986). The Civil War a narrative: Fort Sumpter to Perryville. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Foote, S. (1986). The Civil War a narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Foote, S. (1986). The Civil War a narrative: Red River to Appomattox. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Griffith, P. (2001). Battle tactics of the Civil War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hardee, W. (1990). Hardee’s rifle and light infantry tactics: For the instruction, exercises, and manoeuvres of riflemen and light infantry. (2nd reprinting). Union City, TN: Pioneer Press.

Lubin, M. (2005). The words of Abraham Lincoln: Speeches, letters, proclamations, and papers of our most eloquent president. New York, NY: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers Inc.

Marvel, W. (1991). Burnside. Chapel Hill, NC: North Carolina University Press.

Murfin, J. (1993). The gleam of bayonets: The Battle of Antietam and Robert E. Lee’s Maryland campaign, September 1862. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.

Murray, R. (2003). Legal cases of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Priest, M. (1992). Before Antietam: The battle for South Mountain. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books.

Illustrations:

(1862) Fair Oaks, Va. Prof. Thaddeus S. Lowe observing the battle from his balloon “Intrepid”. Fair Oaks United States Virginia, 1862. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018666175/.

Gardner, A., photographer. (1862) Antietam, Md. Allan Pinkerton, President Lincoln, and Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand. Antietam Antietam. Maryland United States, 1862. October 3. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018666254/.

Mrs. Rose Greenhow. , None. [Between 1855 and 1865] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017895442/.