Disclaimer: I want to be clear, the term well-regulated militias refer to the National Guard and State formed auxiliaries as established by the Militia Act of 1903. Independent and/or private militias will encompass all others who make the claim of being well regulated but may or may not honor United States’ laws.

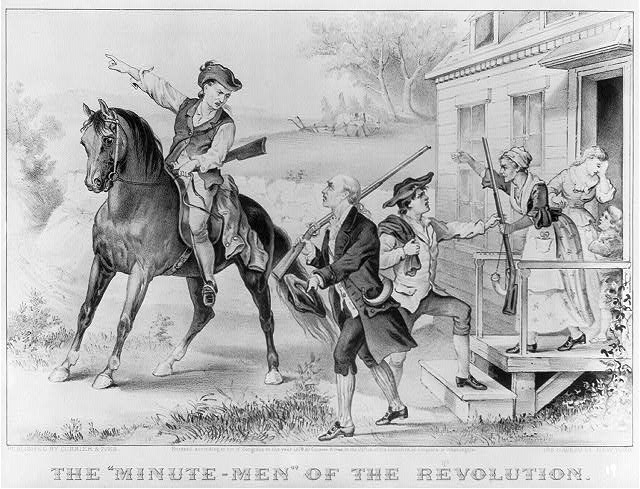

Movies like the Patriot (2000) advocate a hyper patriotic view of the American militias’ grass roots fight to defend a fledgling country, while the movie simultaneously whitewash issues like slavery, treatment of freed slaves, divided loyalties, and tactical failures. Such images of militia harken back to the grade school myths surrounding our country’s quest for independence. The history of the Militia success has largely been overblown in the narrative of the last 250 years of American History. I’m not trying to suggest that militias have not contributed to military successes or fought in some battles as well as regulars, but their inherently unregulated nature during the American Revolution made it incredibly difficult for military commanders to depend on them.

Today unregulated (private/independent) militia groups threaten the very fabric of our society. Empowered by the rapid communication abilities within social media to spread a false message and inflame those with similar ideology, private militias provide the same things to unstable individuals, that the military offers to more balanced individuals without those pesky strict consequences for insubordination, hate crimes, or violations of federal laws which the formal military and National Guard enforce. Why is this so difficult regulate a militia? It’s simple, the standing military in the United States was established first by the Continental Congress and then later defined by the Constitution and is governed under very specific laws, has civilian oversight to prevent coups, and at its core, possesses an altruistic vision that, in our nation, our diversity makes us stronger.

Militias groups, especially in the last 20 to 30 years, are increasingly anti-government, politically polarized, and homogenous (same with respect composition and to ideology). While condemning the lifestyles of religions and cultures they chose not to learn about, tolerate, or understand, these types of militia recruit from an echo chamber which is similarly homogeneous. Militias love to wave the flag but the flag they wave has become unrecognizable to the average U.S. citizen. The flags militias wave often have political logos superimposed or symbols hijacked from the American Revolution or Civil War, or religious messages stenciled across the field. This blog will take a critical look at the history of Militia in the North America and the United States from 1607 to 2021.

In the early 1600s, when Europeans began significant colonies on the Eastern seaboard, militias were organized to protect Christian settlers who were (let’s be completely honest here) encroaching on Native American lands. Encroaching is stressed here because that is what Europeans did, and not just in North America, European did this in South America, India, Africa, and the far East. Under the perceived enlightened concepts of post reformation Protestantism, these settlers also believed in converting indigenous peoples to Christianity, often with violent coercive measures (Tebbel & Jennison 2006). When coercion failed wars of expansion began in earnest by all European power involved in colonizing the New world. Where does the militia play into this, you ask? Well starting with Jamestown and then continuing to Plymouth, no formal military troops were sent to the North America. Since Jamestown and Plymouth were commercial ventures to find gold and relocate religious separatists, these colonies had to rely on mercenaries to defend themselves (Bradford, 2016). As time progressed these mercenaries began training militia to take on defensive and later offensive roles. One only needs to read the frustrations experienced by Captains John Smith (Jamestown colony) (Thompson, 2007) and Miles Standish (Plymouth colony) (Abbot, 2019) to see how difficult militia were to regulate. Under his strict military discipline John Smith managed to guide the Jamestown colony through a period known as the starving times, Smith was eventually wounded in a freak accident (Thompson, 2007) and subsequently forced to leave the colony. Miles Standish had a little more success but was equally frustrated in his endeavors to create a true military organization.

North America 1607 to 1630s:

The site of Jamestown was selected for accessibility to deep draft ships and defensibility from England’s primary threat, the Spanish. The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) was a consequence of Columbus voyages. It was a Papal treaty which divided the New World between Spain and Portugal. Endorsed by the Pope, the treaty stipulated that any lands under control of a Christian king would not be colonized (Bergreen, 2003). Since indigenous people were not under the authority of a Christian king and Spain and Portugal were the only two powers present in the New World at that time, they were the only ones with a claim. England and other European powers would not actively settle in the New World in significant numbers until after the Protestant Reformation. The post reformation government in England sponsored numerous ventures into the New World as did France. Spain jealously guarded its holdings in the New World and posed a significant military threat to any European powers attempting to gain a foothold in the Americas. Spain made no pretense about military conquest, they sent naval and formally trained military ground troops into the New World after Columbus’s multiple voyages. Although a couple of private mercenary type ventures did occur, by in large, Spain’s conquest established an economic lifeline of gold from the New World to continental Europe and they guarded it as jealously as modern billionaires guard their tax returns.

Colonial Militias:

Most European colonies in the North America, possessed some sort of militia ostensibly to protect themselves from Native Americans. Over the course of the first 145 years from 1607 to 1752, conflicts in the New World often mirrored tensions in continental Europe. France and England often employed Native Americans to launch guerilla raids on the frontier of their respective colonies. In these cases local militias were activated to fight these conflicts as well. These militias elected their own leadership which presented unique challenges to the defense of the colony (Bobrick, 1997). It was very hard for militia leaders to maintain control of their members. While activated in a distant sector of a colony, if a member of the militia received word that his home was being attacked, they would often (understandably) desert to protect their family. Over time this became a concern of colonial governments. When militias were activated in the future, they were under individual colonial legislation which provided for more military like penalties for desertion.

While colonist feared standing armies of their leaders in mainland Europe (Bobrick, 1997), they also realized the standing professional military forces operated under discipline and consistent training. When the French and Indian War erupted in North America (essentially an extension of the Seven Years War in Europe), colonies outright requested troops from England to protect their colonies. Now there were very effective militia units that fought on the side of the British and more or less matched deployed British troops in number. Militia of this time period, though raised, financed, and lead by local colonial officers were subordinate to and answerable to the British Military and the Crown in particular. To give an example of this, a lieutenant (a junior officer) in the British Army in the North America could hold military authority over and appointed colonial militia colonel (a much more senior officer) (Bobrick, 1997). Because colonists were loyal to the Crown at this point in history, the consequences of resisting authority in time of war were grave. Washington himself, a militia colonel who tried repeatedly to obtain a royal commission, eventually became General Braddock’s aide-de-camp to avoid being answerable to junior British officers he viewed as beneath him (Bobrick, 1997).

Militia in the American Revolution 1775 to 1783:

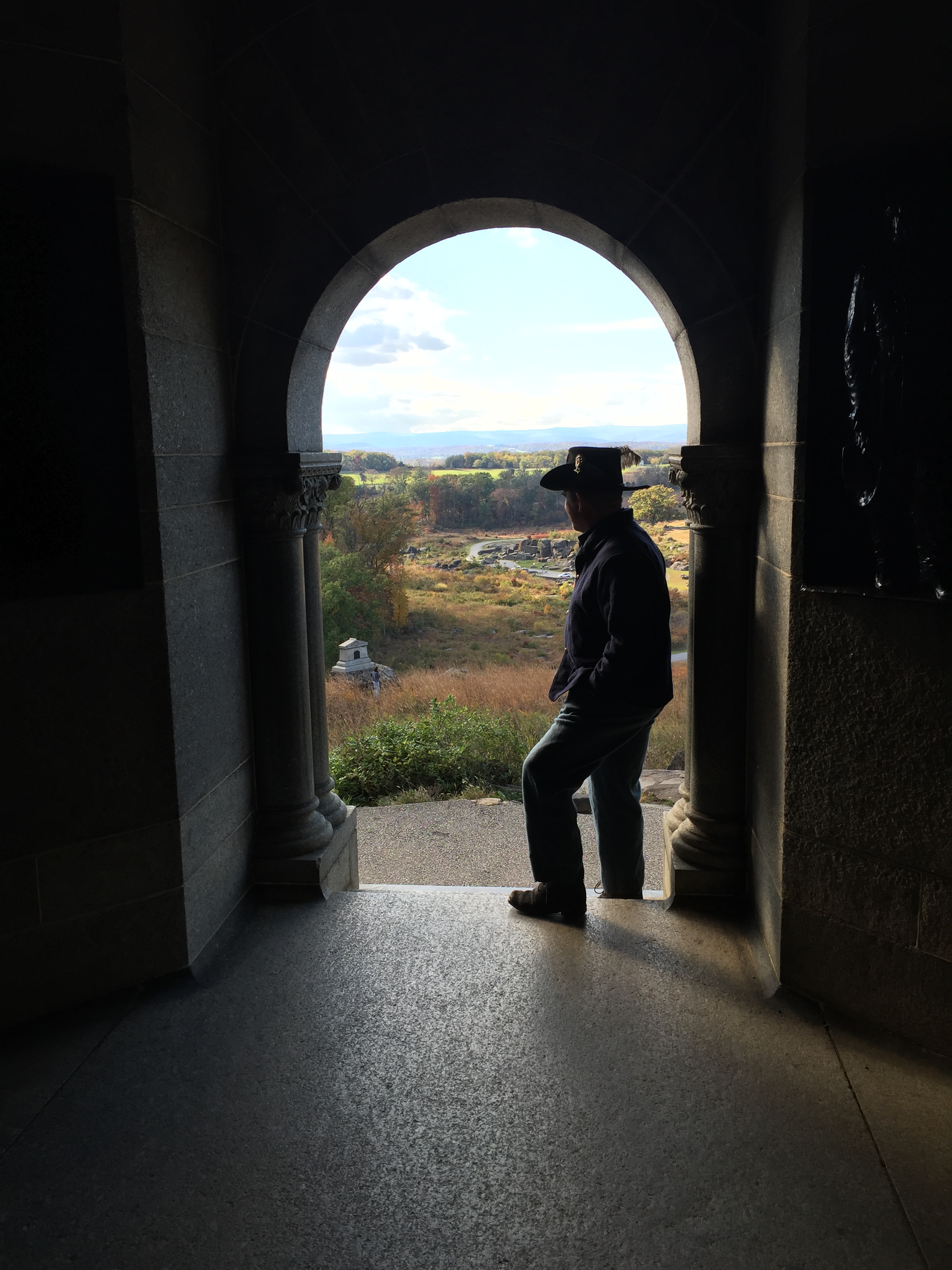

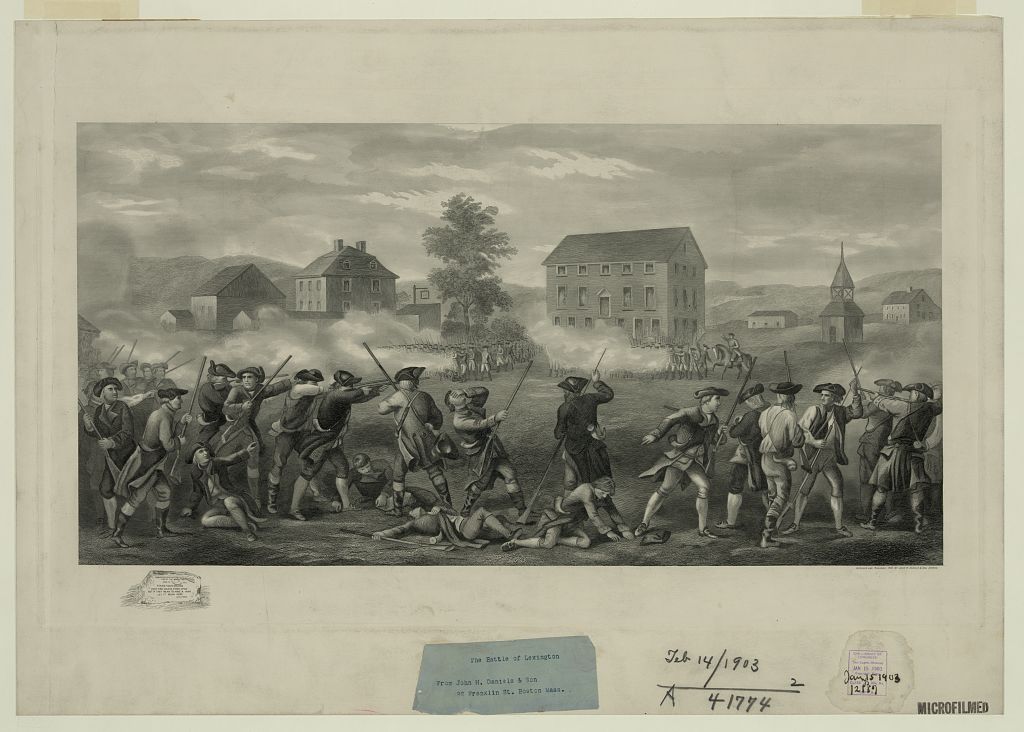

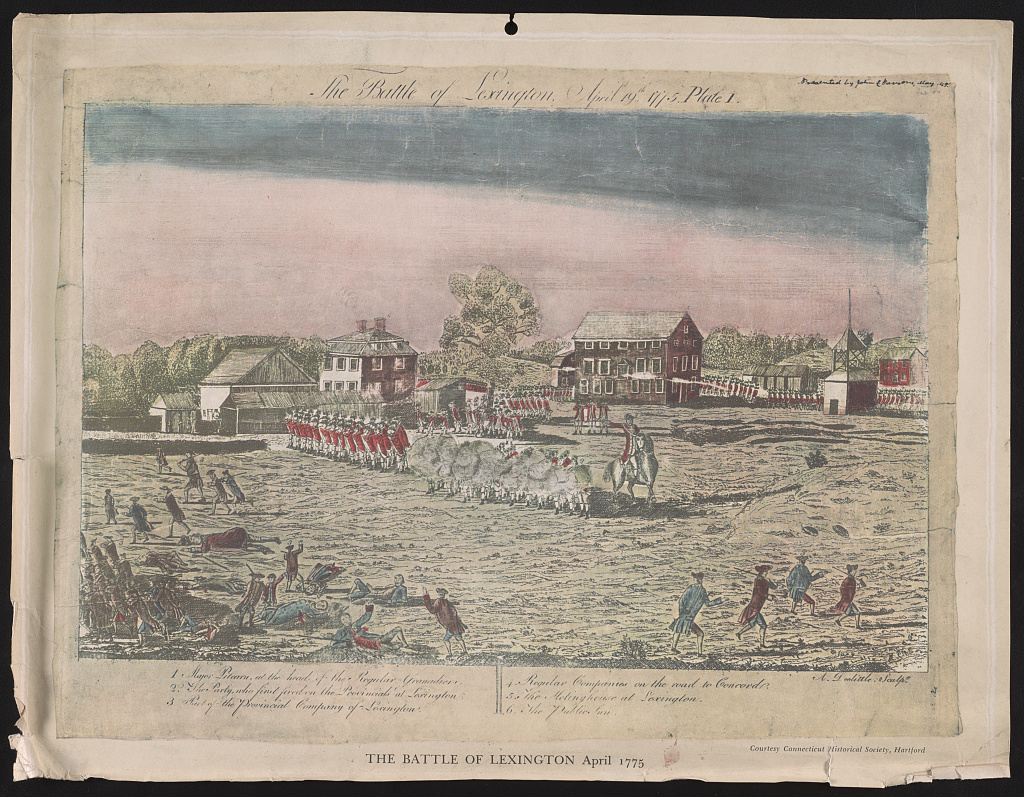

When British colonist began resisting the permanent presence of British Troops in North America and the more heavy handed leadership of colonies by Crown’s appointed leadership, bands of local militias began to actively engage British forces using guerilla tactics (Leckie, 1993). Historical movies love to highlight the roll of the militia at Lexington and Concord against the British. The casualty count was certainly lopsided and impressive, but the British Commander at the time had limited resources and was absolutely dependent on using Boston as a base of operations. There were only about 25,000 British troops on the continent at this time and re-enforcements were 8 to 12 weeks away due sail power and limited communications with Europe (Leckie, 1993). What many U.S. citizens today don’t realize is we fought a war for a little over a year from April 1775 to July 1776 without trying to become independent from Britain. At the beginning of the American Revolution, independence was not even a secondary objective (Bunker, 2014). The colonies wanted autonomy and representation not independence.

Many colonies resisted the move toward independence vociferously, since their interest were primarily agricultural in nature and dependent on trade with the mother country and its naval protections for that trade (Ellis, 2002). The vote for independence was tricky and required the softening of language critical of slavery to gain the support of southern colonies (Ellis, 2002). In June 1775, a little less than a year before the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Army was formed and George Washington was appointed as its Commander in Chief. He would command each colonies forces as a single unified Continental Army (Leckie, 1993). Militias would continue to support this army with varying degrees of success. In many early battles the Continental Army was left holding the bag when militia fled in the face of British soldiers. During his service during the New York campaign Private Joseph Plumb Martin observed the following: “When I came to the spot where the militia were fired upon, the ground was literally covered with arms, knapsacks, staves, coats, hats and oil flask, perhaps some of those from the Madeira wine cellar,” (Martin 2002, p. 32). Washington spent two years keeping the British forces at bay by engaging and redeploying (retreating). His goal was preserve the Continental Army long enough for European intervention from Spain and France (Lockhart, 2008). Where many militia members would come and go in their support of the Continental Army, the soldiers of the Continental Army, representing individual state regiments. These solders remained (for the most part) and endured countless hardships, negligible if any pay, and countless other privations to win our independence.

In 1975 when I was in 2nd grade, I was taught that we won the American Revolution because we wore blue uniforms and hid behind trees and rocks when we fired at the evil redcoats with our Kentucky long rifles. Now many believe that it is much too hard to teach a young child the more complex aspects of our quest of independence but what I was taught was absolute fiction. We did not start consistently winning land battles until we deployed organized army units under strict military command and training with allied help (Lockhart, 2008). Our success was hinged upon the effective use of European stye muskets, artillery, and tactics, delivering massed fires at opposing bodies of troops. Militias were important adjuncts to those forces but they were far from decisive in the big picture of how the war was won. America’s war for independence was won through organized military leadership of disciplined soldiers with some help from militias, economic pressure (thanks to privateers and the French Navy), support of allies (ground and naval forces from France and money from Spain), and diplomacy (Chavez, 2002). No single element alone won our independence but if you want to truly thank someone for our independence, thank maritime insurance companies in Great Britain. Thanks to privateers, insurance premiums rose so much for British ships, that merchants pressured Parliament for peace, so that normal trade could be resumed (Toll, 2006).

Shay’s and the Whiskey Rebellions:

Following the American Revolution, when we operated under the ineffectual Articles of Confederation (AOC I’m sure in modern context this acronym with trigger some people). Inequitable treatment of former solders by business interest led foreclosures and subsequently to a rebellion. Daniel Shay, a Captain in the Continental Army during the Revolution, led a force of organized farmers and discharged soldiers to assault the armory at Springfield, MA (Toll, 2006). When states were petitioned by Congress (we didn’t have a president at the time), many states viewed this as a regional/state issue and not a national issue, so many states ignored the request. Shay’s Rebellion, demonstrated the need for a stronger national government. From Shay’s Rebellion, we had the Annapolis Convention organized by Alexander Hamilton. The Annapolis convention sought to fix some of the problems with the AOC. The members soon realize what was needed was a drastic change. That change would come from the Constitutional Convention (Ellis, 2002).

Following the Constitutional convention, yet another rebellion over the excise tax on whiskey resulting in the use standing military and the calling up of troops from the states to support putting down the rebellion. This was one of the first uses of Constitutional authority and Washington was actually prepared to lead those troops as Commander In Chief (Toll, 2006). Fortunately, as in the Shay’s Rebellion, the crisis was solved relatively peacefully, without executions or a scorched earth policy. Frankly, it’s amazing the AOC functioned as long as it did without the nation falling apart.

The War 1812:

If you want a handbook on how militias hurt a cause look no further than the War of 1812. Let’s be clear, this was really a naval success story not a land forces success story. In the interim years between the ratification of the Constitution and the War of 1812, The United States grew in population, land mass, and wealth but it was not, by any conventional definition, a super power. Under Thomas Jefferson’s administration the military had been castrated, most of the Navy except for six frigates had been placed in ordinary (ordinary was a term for storage) in favor of rather impotent gun boats (Toll, 2006). The expansion of the United States into areas acquired after the Revolution and the territory covered in the Louisiana Purchased left many Native American tribes with the choice of assimilating into U.S. society as third class members (note I avoid using the word citizen) or seek the help of the British in Canada. British sponsored Native American attacks on the western frontier combined with British atrocities on the high seas, compelled the United States to narrowly vote for a war with Britain (Borneman, 2004).

The War of 1812 was not a high point for the United States Army or the militias which supported it. The fall of Ft. Dearborn and the Bladensburg Races, where U.S. forces regulars and militia fled from the British, resulted in an unpopular war becoming more unpopular with the citizenry (Borneman, 2004). Privateers (not quite a naval militia) and our Navy once again drove up insurance premiums on British merchant vessels, just as they did during the American Revolution. The most famous land battle success of the War of 1812 (The Battle of New Orleans) actually occurred after the war was technically over. While this was technically a militia heavy battle and a victory, the militia participants which included some Native Americans, pirates, and some African Americans, did not achieve any enfranchisement for their efforts (Broneman, 2004).

Between the War of 1812 and the Mexican American Wars, militias were largely silent since peace and prosperity were prevalent on the eastern seaboard and most conflict was in the newly acquired western territories. Conflict with indigenous peoples were primarily the responsibility of the very small regular army. During this time States did have various militia originations which met once in a while for some training and politicking subsequently their regulation was very loose. Their uniforms ran the gamut of revolutionary war leftovers and homespun clothing. Many who commanded and/or organized them did so to further their political clout rather than for any truly defensive purpose.

The Civil War:

When the southern states elected to secede from the Union, they did so as a confederacy of independent states. Temporarily without a standing army, many who initially answered the call of their states came from the militia (Foote, 1986). States rapidly began raising regiments of troops. The state troops differed from militia because they were specifically called up by the respective state governments to fight as a collective armed force against the United States. In some instances militias were rolled up into the state regiments. In the north as well as the south, militias performed more of a home guard function (Catton, 1969). In this capacity, they were often viewed with contempt by the regular forces of both sides.

In the South, as the war progressed, the Confederacy passed the Partisan Ranger Act. This would empower private militia forces to run irregular operations, primarily in the frontier regions to assist in the harassment of United States forces (Fellman, 1989). This would also produce some of the most notorious psychopaths and criminals the United States had ever encountered up to this point.. Bloody Bill Anderson, John C. Quantrell, and Jessie James are a few nefarious biproducts of the Partisan Ranger program. Quantrell would continuously try to flex his perceived military authority and be a thorn in the sides of military leaders in both the north and the south. Jessie James would expand his criminal career into the late 19th century long after the war ended. The atrocities committed by these partisans militias often had reciprocal consequences for POWs of both sides (Speer, 2002). Militias in the part of the United States that remained loyal to the Union would often be composed of people to old or unhealthy for front line military service (Catton, 1969). They would protect lines of communication well inside Union territory and would become a strategic necessity in light of Lee’s two invasions and raids by John H. Morgan.

Interwar Years: 1866-1914.

In the time period between the Civil War and World War I, there was not much written about militias. They fell out of favor despite the United States vast territory. What militia groups that did exist, acted more like social clubs rather than a protective force. In this period (particularly in the years of Reconstruction 1865 to 1877) in the south private armed groups such as the notorious KKK engaged in campaigns of voter intimidation of freed negroes (lynching’s, arson and other acts of terror) and harassment of northern businessmen (referred to as Carpet Baggers). The western territories and states had small local groups activated for specific emergencies. By the late 1800s militias were essentially a dying institution.

The National Guard and Militia in the Modern Era:

I have to control myself every time I see someone wearing a shirt that says National Guard Est 1620. The National Guard has its roots in the American Revolution and Civil War with the calling up of state regiments but it was established in 1903 not 1620. We weren’t even a nation until 1776. I love technicalities. The National Guard was established under the Militia Act of 1903. This formalized the regulation of state military forces in the United States. The Militia Act has been revised since its adoption and is now part of Title 10 United States Code Armed Forces (10 U.S.C., 2011). Title 10 has removed the language referencing the unorganized militia as defined in the original act of 1903.

The National Guard has served with distinction in every war since World War I. Like any organization it has its good units and bad units. This variance in quality has more to do with individual unit leadership than history. Since the Gulf War of the early 1990s, the federal government has increased oversight on training of its reserve component units, of which the National Guard is a part. The National Guard has had its dark days. The Kent State massacre 1970 is probably the most famous incident. Like the regular military, the National Guard has also been misused from time to time and sent into impossible situations for which it was neither trained nor properly prepared. The National Guard is a well-regulated militia as envisioned by the Constitution of the United Sates. Governors often falsely believe that the National Guard is their personal army to command but specific regulations are in placed to prevent abuse of powers by governors.

Modern Militia Groups:

Modern militias are not representative of the United States military or reserve components (National Guard and Reserves). With the exception of auxiliaries that require no formal military training such as the Texas State Guard and Kentucky State Guard, modern militias are ideologically rooted, homogonous (except for token members used to claim diversity), and claim to be strict constitutionalist (though they cherry pick which parts of the Constitution they choose to believe or follow. Basically they disregard everything past the first ten amendments). Many do not believe in religious freedoms, rather they believe that religion should be part of the government and the religion they want is more often than not is evangelical Protestant Christianity. In the last 30 years unregulated militias have grown more violent and with the influx of former military members more tactically savvy.

Though Ruby Ridge Idaho and Waco Texas demonstrated how the Federal Government can mishandle situations, it doesn’t change the fact that anti-government groups, some of whom where the title of militia, were every bit as at fault in those sitiations as the government was in its response. Private militias have capitalized on this sentiment to justify their existence. Since these events, private militias have grown not diminished. Those who died at Waco and Ruby Ridge serve as martyrs to the movements and reinforce twisted ideology that private (very unregulated) militias are necessary. Reality is far from this picture.

Many modern private militias are conditioning their members to believe the end is nigh and to prepare for an apocalyptic landscape. Their post-apocalyptic vision has more in common with Salem of the 1600s than it does of the United States of the late 1700s. A short trip though YouTube provides you with an eye opening glimpse into the paranoid and delusional vision these groups perpetuate. Some militia organizations “supported” law enforcement during recent civil unrest giving the illusion that all law enforcement has a high opinion of militia but on January 6, 2021 the true color of their support of law enforcement was evident by their storming of the United States Capital and assault of capital and metro DC police.

Many militias members love to quote Thomas Jefferson which is only appropriate. He believed colored and native American races were inferior to Caucasians of European decent, hated slavery but retained his own slaves, evaded any semblance of courage during the Revolution (fleeing Virginia with Banastere Tarleton hot on his heals), exceeded his authority as Minister to France and Secretary of State, undermined Washington, screwed over his friend John Adams, created the salacious nature of political partisanship in the United States, castrated the military prior to the War of 1812 (leaving his successor with a financial and military mess), and impregnated his chattel. But hey, he gave us the Declaration of Independence so all of his sin must therefore be absolved, right? His most famous quote used by the militia community is undoubtably “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure” (Ellis 1998, p. 118). Such quotes have been used as motivational rallying cries for such radicals as Timothy McVey, Eric Rudolph, and countless political pundits.

Many militia members, gun rights, and (ironically) gun control advocates quote the 2nd Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to solidify their respective positions.

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” (As quoted by Jordan 2007, p. 45).

Militia members believe the clause ‘. . .a well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State’, justifies their position and existence. Gun advocates claim the literal interpretation by the clause ‘. . .the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed’, to justify their position. Gun control advocates believe the clause ‘. . . a well regulated militia’, justifies their position of limiting guns to the National Guard. In reality, no one at the highest levels of our government can universally agree about this polarizing amendment our constitution. Our founding fathers could not visualize, the types of firearms we have today, nor could our founders visualize school shootings, hijackings (as air travel didn’t exist in the 18th and 19th centuries), or voter intimidation with arms. Our founders developed a system of government where no single person, or branch of the government wields absolute power. The unregulated militias would have this changed so that their chosen charismatic leader wields power, and there have been such precedents in history prior to our revolution. Our founders recognized the threat such unregulated forces could pose. After all, world history up to that point and in the modern era is full of examples of militia installing dictators.

The term militia, in the modern context, has become synonymous with extremism, and their members are culpable for that image. Many in the National Guard do not want to be viewed a militia because of this modern image. I know many who serve in the Guard who are very proud of their service and the part of their uniform that says U.S. Army or U.S. Air Force. They wear the same exact uniform that I wore for 21 years in the regular Army. Make no misstate the National Guard is our Nation’s well-regulated militia because it operates under regulations advanced and approved by the people of the Untied State and not polarized ideologs that cherry pick the constitution when it convenient for them to do so. The men and women that make up our nations well-regulated militia (the National Guard) have sacrificed time, energy, and blood to protect our country both domestically and abroad. They’ve expedited recovery after natural disasters and responding to incident of domestic terror and unrest. Are they perfect, far from it, but they take the same oath as everyone else in our nation’s military and are subject to the same level of accountability to the people of the United States and not to a megalomaniac.

References

Abbot, J. (2019). Miles Standish, the Puritan captain. Glasgow, UK. Good Press.

Bergreen, L. (2003). Over the edge of the world: Magellan’s terrifiying circumnavigation of the

globe. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Bobrick, B. (1997). Angel in the whirlwind. The triumph of the American Revolution. New York,

NY: Penguin Books.

Bradford, W. (2016). Bradford’s history of ‘Plymouth Plantation’-From the original manuscript.

With a report of the proceedings incident to the return of the manuscript to Massachusetts.

Lexington, KY: Filiquarian Publishing LLC.

Borneman, W. (2004). 1812:The war that forged a nation. New York, NY: Harper Collins

Publishing.

Bunker, N. (2014). An empire on the edge: How Britain came to fight America. New York, NY:

Ventage Books.

Catton, B. (1969). Grant takes command. Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company Inc.

Chavez, T. (2002). Spain and the independence of the United States: An intrinsic gift.

Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Ellis, J. (1998). American Sphinx: The character of Thomas Jefferson. New York, NY: Vintage

Books.

Ellis, J. (2002). Founding brothers: The revolutionary generation. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Fellman, M. (1989). Inside war: The guerrilla conflict in Missouri during the American Civil War.

New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Foote, S. (1986) The Civil War a narrative: Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York, NY: Random

House.

Lekie, R. (1993). George Washington’s war: The saga of the American Revolution. New York,

NY: Harper Perennial.

Lockhart, P. (2008). The Drillmaster of Valley Forge: The Baron de Steuben and the making of

the American Army. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers.

Martin, J. (2001). A narrative of a revolutionary solder: Some of the adventures, dangers, and

sufferings of Joseph Plumb Martin. New York, NY: Signet Classic.

Speer, L. (2002). War of vengeance: Act of retaliation against Civil War POWs. Mechanicsburg,

PA: Stackpole Books.

Tebbel, J., & Jennison, K. (2006). The American Indian wars. Eddison, NJ: Castle Books.

United States Code Armed Forces 2011, 10 U.S.C. §§ 3001 to §§ 10001 (2011).

Thompson, J. (2007). The journals of Captain John Smith: A Jamestown biography. Washington,

D.C.: Natinal Geographic, LLC.

Toll, I. (2006). Six frigates: The epic history of the U.S. Navy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton &

Company, Inc.

Illustrations

Doolittle, A. & Marian S. Carson Collection. The battle of Lexington April/ A. Doolitle sculpt. Massachusetts Lexington, None. [Place not identified: publisher not identified, between 1940 and 1950] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2015650276/.

(ca. 1903) The battle of Lexington. Massachusetts Lexington, ca. 1903. Boston: Published by John H. Daniels & Son, Jan. 15. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004669976/.

(ca. 1904) Captain Miles Standish. , ca. 1904. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98504702/.

Currier & Ives. (1876) The “minute-Men” of the Revolution. United States New England, 1876. [New York: Published by Currier & Ives 125 Nassau St. New York] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002710565/.

Unidentified soldier in Virginia militia uniform. United States, None. [Between 1861 and 1865] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013650141/.

W. Duke, S. &. C. (1888) Captain John Smith. America, 1888. [Place not identified: Publisher not identified, ?] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2015651600/.